This article was originally published by

iFact.ge

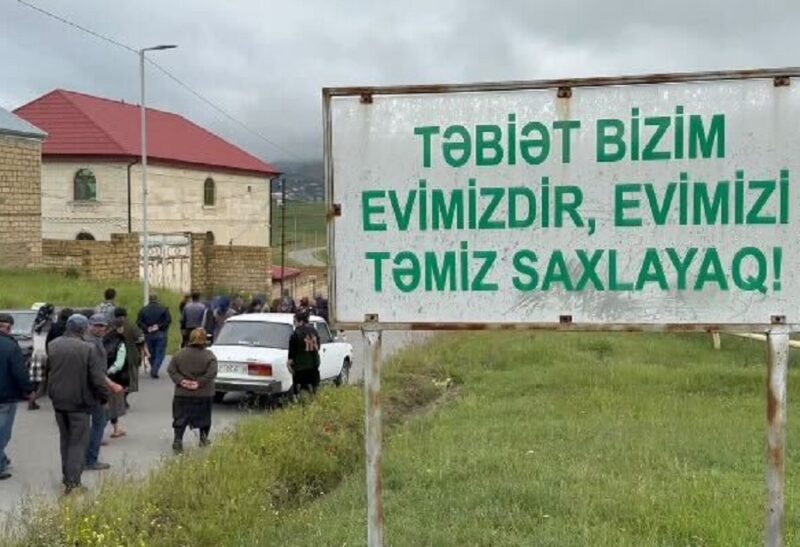

Erisimedi can be translated as “hope of the nation” in Georgian language. But the small Georgian village on the Azerbaijan border bearing that name is one of the more hopeless places in Georgia. Ititala, the village across the border, is no better.

The two countries have failed for over 25 years to untangle border claims that only became relevant after the collapse of the Soviet Union. They sporadically discuss it, but the reality on the ground is a tangle of old fences and trees that has led to property confusion, lost cows, arrests — and one death.

Azerbaijan actively guards the border with armed soldiers in watchtowers and a small military base. Georgia keeps a few guards in the village and operates a vehicle checkpoint three kilometers away on the entry road.

“Nobody knows where the border is,” says one resident who was arrested on October 2017. “Where the border guards stand, we assume that’s the border.”

Few of the 80 or so families living in Erisimedi village, located about 50 kilometers northeast of the Georgian regional capital Signaghi, are natives of the region. Some moved here from the western Georgian region of Ajara in 1989 after landslides. Others are ethnic Chechens who left their villages in the Pankisi Gorge close to the Chechnya border in search of better land or more security.

The Georgian villagers have been hearing reports for at least eight years that Azerbaijan would buy or take control of at least part of their land. Now the villagers on the two streets running closest to the Azerbaijan side are hearing talk that they are already living on Azerbaijan land.

Erisimedi villagers’ cattle gather daily near the Alazani River, which would form a natural boundary. but is only about 10 meters wide here. If cows cross the river, their owners are afraid they will be shot if they go get them. Villagers claim as many as 500 cows have been lost in the last 25 years.

In 2010, 15-year-old Akhmed Ibragim Gaurgashvili was killed by Azerbaijan border guards. Eyewitness Emzar Sumanidze says Gaurgashvili climbed a fence to go after a cow, and was immediately shot in the head.

“He was bleeding badly,” Sumanidze says. “Other people were in the trees gathering firewood. They couldn’t get to him, so they ran back to the village screaming that a boy had been shot.

“We could hear him asking for water. But he was maybe five meters over the fence, and nobody could help him. He died.”

The Azerbaijan State Border Service tells a different story. They say three Georgians walked over the border and were ordered to stop. When they continued to walk, the Border Service admits one was shot and killed.

Gaurgashvili’s family left the village shortly after his death and returned to the Pankisi Gorge. His mother says today that nobody has ever told her the name of the man who killed her son.

“They killed my innocent son,” says Asmat Gaurgashvili. “But no one was arrested and put in jail.

“I was shown an investigative report that my son was killed on Georgia territory, not Azerbaijan. Is it not a crime? Why did our government do nothing?”

Taliko Makharadze, 76, lives on one of the two main streets in Erisimedi. She says people are moving from the village because of the border confusion. She says neighbors across the street can’t get their land legally registered, but she could.

“People say that Georgia finishes in front of my door,” she says.

Those caught by border guards are generally held a few hours and then released after paying a fine. People on both sides are supposed to get permission documents that allow them to go near the border with their cows and to collect firewood. But according to Makharadze, only about five of the 80 Erisimedi families currently have documents.

“I used to have permission, but I was arrested in 2015 by Georgian border guards while gathering firewood, and now I can’t get permission,” says Makharadze. “We go to the notary at the local bank and we wait for a long time, and then we are told there are no documents.”

Makharadze says she has lost eight cows since she has been barred from going into the trees or near the fences.

Ititala village has mostly Georgian speakers who are called Inglos. Many were born there, and many have converted to the Muslim religion.

More Ititala villagers have permission documents than their Georgian neighbors. They apply to the regional municipality, who sends them to the Azerbaijan State Border Service for approval.

Seyfulla Balayev was arrested once by Georgian border guards when he tried to get a cow that had crossed into Georgia.

“I had a permission document to take my cows near the border,” he says. “Three of them went to the Georgian side, and only two came back. I tried to get the third one, but suddenly I was ordered by Georgian soldiers to stop, and I was arrested by them. Azerbaijani soldiers took my permission document away.”

According to his neighbors, Balayev received new permission papers after someone decided he was still on Azerbaijan territory when he tried to get his cow.

One Ititala villager was arrested for being five minutes too early: ”A man called out to me and told me to come help him clean up some brush. Unfortunately, it was 7:55 am. According to regulations, you only have access from 8 am to 8 pm.

“So I was arrested by Azerbaijani border guards and fined 250 manat (about $US150). I don’t have the money to pay it, and I’m not allowed to leave the country and go to Russia and earn the money.

“I told them a forest guard had called me, and they asked him and he confirmed it. But it didn’t matter. Now I can’t take my cows anywhere.”

Ramazan Rahimov, 80, was born in Ititala. He says he owns land right at the border.

“When I go to my land, I show my permission document to Azerbaijani soldiers. But if you go too close to the border, you are going to be arrested.

“I don’t see cows coming from the Georgian side. If cows cross the border, the soldiers (on each side) will tell each other, and one of them will take the cow back.”

Erisimedi villager Emilion Kborvashvili disagrees. He says he lost three cows and he has no idea who got them. “Is it the (Azerbaijan) soldiers?” he asks. “Where we can complain? Sometimes soldiers bring our cows back, sometimes not.”

Neither local nor national officials want to talk much.

Ititala chief executive German Balayev was hostile to journalists on two visits. “Our village loses five or six cows a year,” he said. “But stealing is impossible, because nobody here would buy these cows. If their cows come to our side, our soldiers always take them back. If they are missing, probably wolves are eating them.

“Two or three days ago, one cow appeared in our village. The Georgian side says it does not belong to them, and our people say the same. We do not know who this cow’s owner is.”

Erisimedi chief executive Ioseb Tsetskhladze concedes villagers cannot follow their cows near the border.

“If a Georgian border guard sees a cow, he sometimes call someone from the village to come get it. Sometimes border guards from both sides get involved,” Tsetskhladze says.

“But those fence posts are a serious border. And there are some spots near the river where it is difficult to see what is happening. Then it becomes a problem.”

At the national level, the villages are a negotiating point in a bigger fight between the two countries over land within and adjoining the 6th-century David Gareja monastery complex.

Azerbaijan Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Hikmat Hajiyev says both sides will try to take into consideration people’s problems. “Azerbaijan and Georgia are neighbors and friend countries,” he said. “These issues are resolved through diplomatic channels. The procedure is still ongoing.”

The Georgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to letters from iFact. A 2014-2018 government strategy states that border agreements will be reached.

Deputy foreign ministers Khalaf Khalafov (Azerbaijan) and David Dondua (Georgia) met in April, 2017. The two sides are scheduled to try again in 2018.

Erisimedi villager Sumanidze , who witnessed the death, is waiting. “It’s a different Georgia here — AzerGeorgia,” he says. “They need to define the borderline. We don’t want to be waiting for more bullets.”